The relationship between the coach and the client is, of course, a fundamental pillar of coaching.

In most cases, coaching relationships are positive, respectful, constructive, empathic, caring and collaborative.

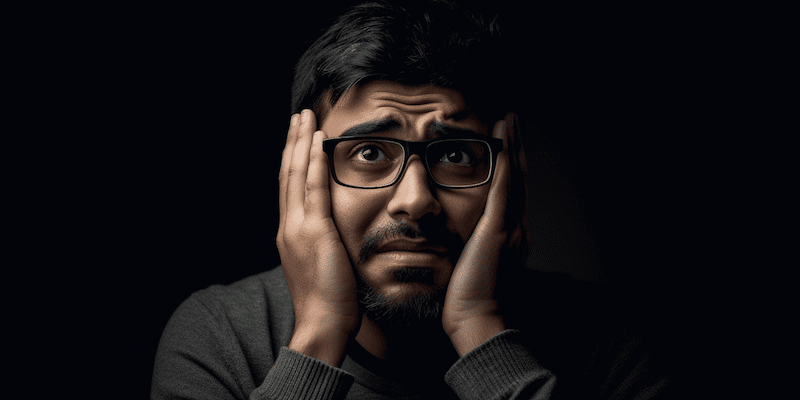

However, as with any kind of relationship, there will inevitably be times that coaches encounter individuals who challenge their skills or expectations, leaving the coach stressed, anxious, annoyed, impatient or any number of other emotions.

As a coaching supervisor, I often hear coaches talk about “difficult clients”.

Ahhh! It’s that darn client being difficult. It’s all down to them.

In this article, I will challenge the term “difficult client” and explore other ways to think about what might be going on.

Of course, this is not to say that the client is not posing the coach difficulties, but, as we will see, the term itself is problematic in both placing the blame squarely on the client and in enabling the coach to avoid exploring their own part in the relationship.

Interestingly, I first encountered this challenge to the terminology early in my coaching career when I spoke to an experienced therapist and brought up the topic of “what to do about difficult clients”.

The therapist gently challenged my language and I can recall a slight feeling of annoyance that this was ignoring the reality and that some clients really are “difficult”!

Of course, the therapist was right. It is an unhelpful term because it implies the client is “difficult” in and of themselves rather than as a result of the coaching relationship we have formed.

Let’s take a look at all this in more detail.

Unpacking the Concept of the “Difficult Client”

The term “difficult client” is one that is heard in every client-focused profession – from Accounting to Zumba Instructing!

Boiled down to its essence, it describes any client who presents challenges in the working relationship and who doesn’t seem to conform to the expectations of the service provider.

The accounting client who gives their paperwork at the last minute and the Zumba student who bustles into the class 5 minutes after it’s started.

In the coaching field, this might be behaviours such as habitual lateness to sessions, seeming resistance to change, an apparent lack of reflective capacity, or even not paying for the service on time.

The term ‘difficult’ is problematic, however, because it inherently passes judgement, implying that the issue lies solely with the client.

Look at my examples above again and you’ll see I purposefully added words like “seeming” and “apparent”.

Someone might “seem” to be resistant but we don’t actually know that they are. It’s only how we experience them.

Not only can this projection of blame create a negative bias in the coach’s approach towards the client, it also lets the coach “off the hook” from reflecting on their own part in the relationship.

This element of self-reflection is a critical piece of the puzzle that is often overlooked but is vital if a coach is to continue to deepen their practice and build ever more effective coaching relationships.

Owning the experience of the “difficulty”

If we are going to own the experience of a “difficulty” then as coaches we need to take a step back and see this as a relational dynamic.

Stating that a coach “finds a client difficult” places the experience of difficulty within the context of the specific coach-client relationship and allows the coach to explore where the problem is arising.

This description is subjective and acknowledges that the perceived difficulty could be due to a variety of factors, including the coach’s personal reactions, biases, or limitations.

It emphasises the fact that the dynamic is influenced by both parties involved and not just a characteristic of the client.

Note, this does not mean that the problematic behaviour is not coming from the client – it might be – but it ensures that the coach allows for the possibility that they have a part to play in the difficulty arising.

Now, you might argue that something as obvious as the late payment of fees is clearly coming from the client.

However, even this might be resolved by the coach being clearer with the client at the outset. Perhaps the coach doesn’t normally feel the need to stipulate this since clients normally pay on time. Thus when a client pays late, they seem to be the problem. They become the “difficult client”.

Likewise, the coach might find a client “difficult” if the client’s communication style clashes with their own, if the client’s expectations of the coaching process are not aligned with the coach’s approach, or if the client’s goals or values are significantly different from the coach’s.

It’s also important to remember that what one coach finds difficult in a client might not be an issue for another coach due to their different experiences, skills, and perspectives.

So in reframing “difficult clients” to “clients a coach finds difficult”, the focus shifts to understanding and adapting to the unique dynamics of each coach-client relationship.

It promotes a more constructive perspective, fostering growth and learning for both the coach and the client.

Rather than seeing the client as a problem to be managed, the client becomes a partner in a shared journey of development and growth.

With all this in mind, let’s take a look at some common experiences that coaches have that may be experienced as difficult, and explore what might be happening and what the coach might do.

Common Client Behaviours that a Coach May Find Difficult

Resistance to Change

The client consistently does things which mean they remain stuck in their current patterns and habits, impeding their progress and leaving them frustrated.

Perhaps they don’t follow through on agreed actions, or they reply “I don’t know” to most questions that go beyond fact-finding, or they keep changing the topic of the coaching.

The coach might interpret this as a “resistance to change” and find this difficult. They might inwardly groan, “So why have you even come to coaching?!”

Psychological/Situational Factors:

However, resistance to change is simply a label we apply to behaviours we have not yet fully understood.

Resistance to change often stems from fear – fear of the unknown, fear of failure, or even fear of success.

It can also stem from a lack of clarity, from overwhelm, confusion and uncertainty.

The client might also be grappling with a fixed mindset, which hinders them from embracing growth and change.

Relational Factors:

In terms of the relationship, perhaps the coach is expecting too much too soon and has not realised that their impatience is feeding the client’s anxiety.

The client might need more time to feel into what they really want yet the coach is overly-eager to get a clear goal.

The coach might need to step back from seeking progress and instead focus on helping the client understand their current state – this relates to the Paradoxical Theory of Change I have written about elsewhere.

At a deeper level, there may be countertransference at play. Perhaps the client’s seeming resistance to change reminds the coach of someone from their past who triggers an emotional response such frustration, impatience or even anger. This might, in turn, be felt by the client.

Coach’s Considerations & Action:

Patience and empathy are crucial.

Explore with the client what is going on and what is leading to the current impasse. Be transparent and engage in dialogue to explore this.

The coach may also explore their own feelings about the sessions and client with a coaching supervisor.

This is a powerful way for them to become more aware of any countertransference at play or any expectations that they are imposing on the client.

Unreliability

Issue:

The client frequently cancels sessions, arrives late, or fails to complete assigned tasks.

This behaviour disrupts the flow of the coaching process and leaves the coach feeling like the client isn’t taking the coaching seriously.

Psychological/Situational Factors:

This could be indicative of poor time management skills, a lack of commitment, or low motivation levels.

It could also signal that the client is overwhelmed, either by the coaching process itself or other aspects of their life.

Relational Factors:

Unreliability might also be a reflection of the quality of the coaching relationship. As the title of the movie goes: “Maybe he just isn’t into you”!

It is always worth reflecting on the quality of the coaching relationship and being honest with oneself.

If rapport is absent or fading, it would not be surprising if the client has a certain reticence about showing up.

Coach’s Consideration & Action:

An open and honest conversation about this with the client can be the best way forward. It can be tempting to try to solve the relationship by imposing stricter conditions – “can you be sure to be here on time” – but my experience shows that talking about it is more effective.

It might also be that the coaching needs to be refocused on the client’s experience of life at the moment if it turns out that self-management is the issue.

Unrealistic Expectations

Issue:

The client expects immediate results from the coaching, leading to disappointment and frustration when these expectations are not met.

Psychological/Situational Factors:

This could be due to a lack of understanding about the coaching process or the nature of their goals.

The client may also be comparing their progress with others, leading to unrealistic expectations.

Relational Factors:

Perhaps the client is projecting an almost saviour like role onto the coach, not recognising that coaching is neither a panacea nor something that creates quantum leaps in outcome.

Equally, it is possible the coach “oversold” themselves in their marketing or consultation, setting up a dynamic of being the “fixer”. The contract between much coach marketing and coaching practice can be stark!

Coach’s Consideration & Action:

Have a clear conversation about the coaching process and timeframe to help align expectations.

It may be worth re-contracting and exploring again the nature and purpose of coaching.

Lack of Engagement

Issue:

The client seems disinterested or unmotivated during coaching sessions. They may not participate actively in discussions or agreeing actions.

Psychological/Situational Factors:

The client may be experiencing burnout, depression, or anxiety, affecting their engagement levels.

Alternatively, they might not find the coaching sessions relevant or beneficial. Perhaps the coach has not helped the client get clear on what’s really important and both are “playing the game” of coaching without getting under the surface of what’s needed.

Relational Factors:

There may be deeper undercurrents of transference or countertransference that are affecting the relationship. Perhaps the lack of engagement is a reflection of how the client feels about the coach or the unconscious dynamics that have been created.

Finally, and to throw a curveball here, perhaps it is not the client who is not interested but the coach and what is going on is a form of projection that, in turn, is leading the client to disengage.

Coach’s Consideration & Action:

Explore the reason behind the lack of engagement.

Adapt the coaching style or content to better suit the client’s needs. If a mental health issue is suspected, refer the client to a suitable professional for further support.

As always, the coach may explore this in supervision to see how they are personally experiencing the client and the extent to which this may be as much a reflection of themselves as it is of the client.

Dominating Conversations

Issue:

The client often talks excessively during sessions, leaving little room for the coach to provide input or steer the conversation.

For a coach this can feel extremely frustrating since it seems to prevent them doing the very thing they are there for.

Psychological/Situational Factors:

This could be a way for the client to avoid addressing challenging issues or receiving feedback and reflections from the coach.

They may also lack self-awareness about their conversation style or they may be anxious, using excessive talking as a coping mechanism.

Some people even think this is what coaching is for, which can often point back to the contracting.

It may also be how the client processes information. Early in my coaching career, I had a client who would spend the first half of each session reading all the notes for the journal of her week. When I finally shared with her my experience of it and the sense of frustration I felt building, she was able to share how it helped her but also to agree on a more effective way for us to work together.

Relational Factors:

The coach and client may have established a talking/listening dynamic early in the coaching relationship that has solidified into a pattern.

The same client with another coach may behave entirely differently because the coach contracts differently, or interrupts to change the nature of the dialogue sooner.

Perhaps the coach was playing it safe in the early sessions but not wanting to interrupt the client’s flow only for this to become a psychological contract – “I talk, you listen”.

There may also be a deference threshold (a term created by Nick Smith) situation here in which the coach feels unable to challenge and interrupt the client due to some sense of inferiority or intimidation.

Coach’s Consideration & Action:

Develop strategies to manage the conversation effectively, such as setting specific discussion points or time limits for each part of the session.

Empathetically but assertively interject when necessary, and provide feedback about the importance of balanced communication in the coaching process.

And, surprise surprise, I would add, of course, explore this in supervision to understand what is going on that prevents the coach from changing the nature of the dialogue.

Importance of Self-awareness and Empathy in Coaching

Hopefully, we are seeing now that the challenge with ‘difficult clients’ is often not them, but rather our reactions to them.

Self-awareness is crucial in managing these reactions.

It entails recognising our own biases and preconceptions, and acknowledging how these could be affecting our understanding of our clients.

Alongside self-awareness, empathy plays a major role in a productive coaching relationship. It’s about recognising and understanding the feelings and perspectives of the client, communicating this understanding to them, and using this knowledge to guide your actions.

When we empathise, we step into our client’s shoes, which can often illuminate why they might be acting or reacting in a certain way.

This understanding can inform our approach and help to build a stronger, more effective coaching relationship.

Key Takeaways

One of the factors that can make a client challenging is a misalignment of expectations. In many ways, this can be seen in all of the examples above.

As a coach, it’s your role to ensure that the coaching objectives are understood and agreed upon by both parties. This understanding provides a road map for the coaching journey, with clear signposts indicating the desired direction of travel.

It’s also your role to manage expectations of what coaching can achieve. All too often the desire to secure clients can, consciously or unconsciously, lead to a mispositioning of coaching’s potential.

This can be a delicate process, requiring tact and understanding. Acknowledge their aspirations, but guide them towards more attainable goals, explaining why these will be more beneficial in the long run.

Throughout the examples above, we have seen how the source of the “difficulty” the coach experiences may be the relationship between the coach and client.

Sometimes this can be a simple thing to get right – a transparent conversation about what is happening in the coaching relationship can be sufficient – but at other times there is a need for deeper reflection on the part of the coach.

That’s where coaching supervision comes in.

The Role of Coaching Supervision

Coaching supervision plays a crucial role in helping coaches navigate challenges they may face with clients, including those they find difficult.

Coaching supervision can support coaches in several ways, including:

Reflection and Insight:

A supervisor provides a safe and confidential space for coaches to reflect on their practice, including their work with difficult clients that they find challenging.

They help the coach explore these situations more deeply, facilitating insight into the dynamics at play.

They can assist in unpacking the coach’s reactions and feelings, fostering greater self-awareness.

Perspective and Objectivity:

As an external observer, a supervisor can offer a fresh perspective on the coach-client relationship, which might be hard for the coach to see while in the midst of the situation.

They can help identify patterns, biases, or blind spots that the coach may have overlooked.

Skill Development:

Supervisors can support coaches in developing and refining their coaching skills.

They can provide feedback and suggest strategies or techniques that the coach might use to manage challenging client behaviours or situations more effectively.

Emotional Support:

Working with clients that a coach finds difficult can be emotionally draining.

Supervisors provide emotional support, helping coaches manage feelings of frustration, doubt, or stress that might arise from these challenging situations.

Ethical Guidance: In situations where a coach is facing a complex ethical issue with a difficult client, supervisors can provide guidance on the best course of action in line with professional standards and ethical guidelines.

Resilience Building:

Supervisors can help coaches build resilience and develop coping strategies for managing challenging client situations, promoting self-care and reducing the risk of burnout.

In essence, coaching supervision is a supportive resource that coaches can draw on to navigate complex client relationships.

It’s a space for reflection, learning, and growth, enhancing both the coach’s professional development and the effectiveness of their coaching relationships.

Conclusion

Understanding and managing complex client relationships is an integral part of being an effective coach.

It’s about maintaining resilience, empathy, and patience in the face of challenges. The reward is in successfully navigating these relationships and witnessing your clients grow and flourish.

There are times, however, when a client can feel difficult.

However, more often than not the difficulty they present is a reflection of a deeper issue or a situation that the coach has not seen.

The client may be overwhelmed, uncertain or fearful.

The coach may be the same!

The relationship may have become bogged down in unconscious dynamics of transference, countertransference and projection.

Or it might simply be that the coach and client need to revisit the aims, methods and agreements of the coaching.

My advice is, before talking about “difficult clients”, take a step back and reflect on what else might be the cause of the challenge.

- Author Details